Toast To Olde Tymes – Lucy Christie Drage

When Lucy Christie Drage died in September 1965, our scribe wrote: “Gallant was the word for this indomitable woman whose life was touched by an over-abundant share of tragedies. Three generations of localites remember her in distinctly different lights. Courtly gentlemen who were gay blades after the turn of the century recall the beautiful Lucy Christie, the acknowledged belle of the Town. Early patrons of her “chintz shop” as well as those who visited Lucy Drage, Inc., in more recent years knew the gifted interior designer who was fondly called “the Elsie de Wolfe of Kansas City” by her A.I.D associates. Young art students found much to admire in her painting style and her feeling for colors.”

Lucy was born on September 18, 1876. She was the daughter of Eda Duhring Christie and C.C. Christie (his initials stood for Charles Cushing). Her father was a grain broker, and the Christies lived on Aldine Place in Quality Hill. Lucy was a student during the early days of The Barstow School. She began taking classes at the Kansas City Art Institute in her girlhood, and continued throughout her life. Lucy preferred to work in crayons and watercolors. An 1895 Kansas City Times article headlined “Beauties At High School” stated, “Miss Lucy Christie is a brunette of delicately tinted complexion and is possessed of considerable dramatic talent, having appeared in a number of plays that have been given by the various literary societies. She has also written a play entitled “Over the Garden wall” which has been bid for by several theatrical managers.”

When the Century Ball was held on December 31, 1900 in Convention Hall, Lucy was there. She was widely acclaimed as the belle of the Ball. Around that time, she met Francis B. Drage, an Englishman. He was a member of the British army and a veteran of the Boer War. “I had some English friends on Warwick Boulevard and I met him through them,” she told the Kansas City Star decades later.

Lucy married Francis on November 12, 1901. Three children were born to the union: two sons, Charles and David, and a daughter, Elizabeth, who was known as Betty. During the early years of their marriage, they lived in England, returning to Kansas City following Francis’ retirement from the army in 1913. Lucy’s mother died in 1914 and her father in 1916. Lucy’s father had owned land in the environs of 76th Street and Indiana Avenue, and she managed the property after his death.

In September 1922, Betty Drage married Frederick Henry Harvey. The groom was named for his grandfather, who founded Fred Harvey, a company known for restaurants, dining cars, and hotels. The young man had been an aviator during World War I and was an executive in the family business. The wedding was a grand event, and the young Harveys would be prominent in Kansas City society for the rest of their lives.

|

| In the garden – a tangled retreat of verdant loveliness with Mrs. Drage at one corner of her lily pool. Reprinted from the August 14, 1937 issue of The Independent. |

Around the time Lucy turned 50, her life began changing in significant ways. 4348 Locust Street became her permanent address. Francis took up residence in England. (In later years, Lucy was known as “Mrs. Lucy Drage,” rather than as “Mrs. Francis Drage.”) Her sister, Mary Firth, moved in with her. Lucy opened an interior design firm, which bore her name. Through the years, the client list included The Kansas City Country Club, the Kansas City Club, and sorority houses at both the University of Missouri and The University of Kansas, in addition to the owners of private homes. Lucy had no training, but Ethel Guy, who was her business partner, did. What Lucy had was an eye for what she liked. As Lucy told the Kansas City Star in September 1929, “a fireplace and dogs about and flowers – chintz flowers! – are a good start toward furnishing a home.” The firm’s original location was on Broadway, but it soon moved to 320 Ward Parkway on the Country Club Plaza. She also became a sought-after speaker. Her home and career would provide some stability during the heartbreaking years to come.

The 1930s ushered in an era of deaths. Her younger son, David, was 26 when he died in a one-car accident in Virginia in 1930. (The driver of the car, Elizabeth Walter Converse, was also killed. She was the estranged wife of James Vail Converse, a prominent New York banker. The crash made the front page of the New York Times.) Francis died unexpectedly in July 1935, not long after the marriage of the Drages’ son Charles to Rowena Hames in England. Early the next year, Betty Drage Harvey visited Rowena and Charles, meeting their infant daughter, Elizabeth Mary, just after her birth. In April 1936, on the final leg of her trip home, Betty died in a plane crash in Pennsylvania, along with her husband, who was the pilot, and their dog. (This accident also was reported on the front page of the New York Times.) Lucy and Betty’s sister-in-law, Kitty Harvey, should have been able to comfort each other. Instead, they became enmeshed in a lawsuit that was ultimately settled out of court. (Lucy’s financial situation improved in the aftermath, but it’s impossible to say that she “won” anything. The circumstances were too dreadful.)

At the start of the 1940s, when Europe was embroiled in a war that the United States hadn’t yet entered, Lucy was the chairman of the local chapter of Bundles for Britain. The organization shipped knitted goods, medical supplies, bedding, and other items across the pond. Some of the people closest to Lucy’s heart were there.

On September 20, 1941, The Independent published a charming story about Lucy and Alexander Woollcott, who was a drama critic and radio personality in New York. (He is best remembered as a member of the Algonquin Round Table, along with wits such as Dorothy Parker and Robert Benchley, and as the inspiration for the Kaufman and Hart play, The Man Who Came to Dinner.) Aleck, as he was known, was the younger brother of Julie Woollcott, one of Lucy’s childhood friends.

“The very nicest way yet devised to celebrate one’s natal day, is to put the presents in reverse. Just so, did Mrs. Lucy Drage on Thursday last. Her devoted friend, Alexander Woollcott long distanced that he would be in England on her birthday and would telephone her son, Charles, and his family. Mrs. Drage pronto speeded gifts for him to deliver.

“To daughter-in-law, the former Rowena Hames, went luxurious silk stockings; coveted razor-blades for Charles and his father-in-law, Mr. Samuel Hames, and to her only grandchild, Elizabeth, a pretty pinafore and a bangle bracelet which was worn by Mrs. Drage’s daughter, the late Mrs. Fred Harvey, formerly Betty Drage, when she was a little girl.”

|

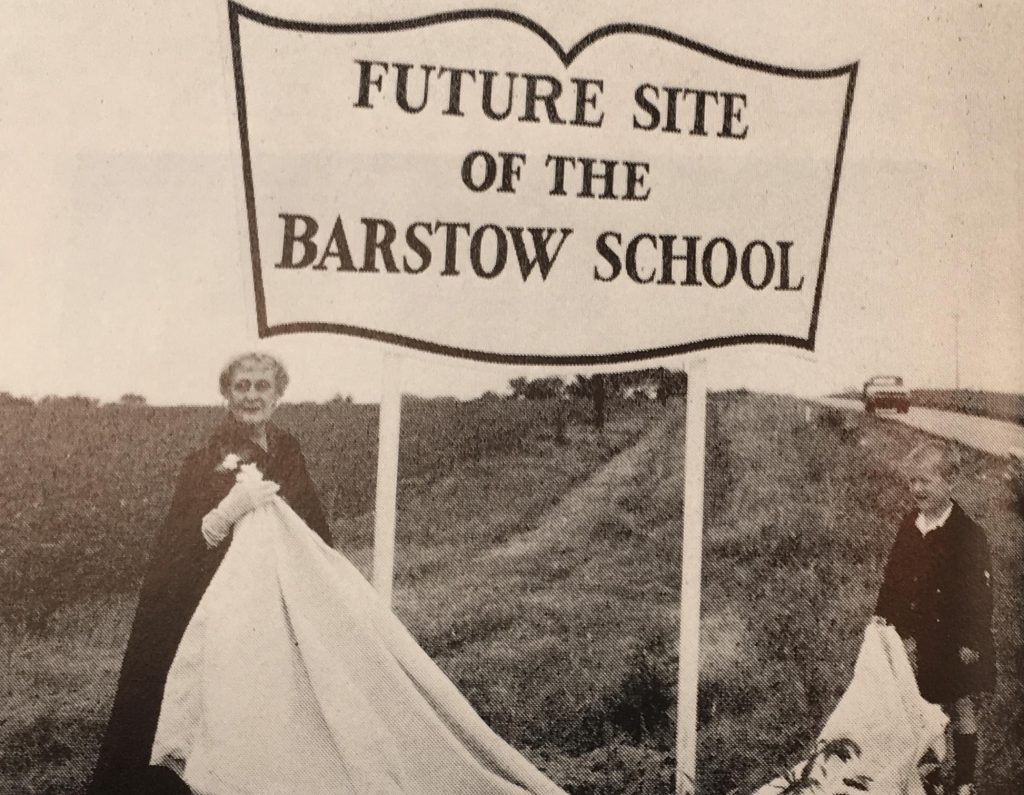

| Mrs. Lucy Drage, assisted by Webster Townley Thompson, 4th generation Barstow-ite, unveils the site of the new school, 115th and State Line. Reprinted from the June 6, 1959 issue of The Independent. |

As unimaginable as it may seem, June 1943 brought the news of Charles Drage’s death. All three of Lucy’s adult children had died in a span of less than 13 years. Lucy persevered, continuing with her work and her hobbies. Her granddaughter’s visits were among the highlights of her later years. Lucy was honored by Barstow in 1959, during the school’s 75th anniversary celebrations. As our scribe noted, the school’s tribute included these words: “Your youthful beauty is a legend, often retold in Kansas City. Your beauty glows today, reflecting the integrity and character within.”

Marjean Phillips (later Busby) wrote a profile of Lucy for the Kansas City Star in July 1964. She described the house on Locust Street where Lucy and Mary lived: “Period furniture and plants fill the small rooms. The modern touch is the color scheme. The living room has a pale gold carpet, mustard-yellow walls and chintz upholstery on unmatched chairs in midnight blue, gold and green tones.” Lucy was, in her own words, “semi-retired” at that point. She was then sharing an art studio at 45th Street and State Line Road with a group of friends. A photo showed Lucy holding a portrait she had created. A little more than a year later, Lucy died on September 11, 1965, exactly one week prior to her 89th birthday.

For further reading: Fried, Stephen. Appetite for America: how visionary businessman Fred Harvey built a railroad hospitality empire that civilized the Wild West. New York: Bantam, 2010.

Also featured in the August 22, 2020 issue of The Independent

By Heather N. Paxton

Features

When Martha Deardorff Shields and Edwin W. Shields began building Oaklands, they had been married for more than a dozen years and were the parents of a daughter and a…

Who remembers Alexander Woollcott? For some, what comes to mind is that he was a member of the Algonquin Round Table and a writer for The New Yorker magazine during…

The third floor of Emery, Bird, Thayer was the site for a May 1937 fashion show featuring everything from beach togs to gardening overalls to bridal dresses, as they were…