THE MORE THINGS CHANGE: New play uses tender family story to address Kansas City’s racial history

Michelle Tyrene Johnson uses theater to tackle big issues. In more than a dozen full-length and longer one-act plays, and in numerous shorter works, she has often found that art can exert a greater impact than a simple recounting of facts. The Green Book Wine Club Train Trip, for instance, given a winning production by KC Melting Pot Theatre in 2019, used wit and ground-level human interactions to examine what travel was like for Black women in Jim Crow-era Missouri.

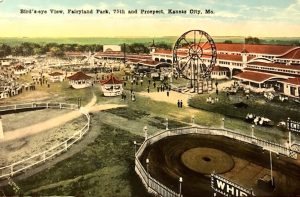

Her new play, which runs through March 5th at The Coterie Theatre, addresses an issue even closer to home for many Kansas Citians: segregation at Fairyland Park, which before the Civil Rights Act was open to Black patrons for one day a year, generally toward the end of the summer.

Commissioned by The Coterie (with a $30,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Arts) and originally scheduled for the 2020-2021 season, Only One Day a Year examines the effect of Jim Crow on a teenage girl in 1960 who simply wants to give her little brother the thing he wants more than anything in the world: to ride Fairyland’s rollercoaster on his birthday.

It is the kind of play that Michelle loves to write: It confronts historical events with accuracy but works its way into our hearts by focusing on the personal drama of Teenage Rose and her brother, Frank. We grasp the enormity of social upheaval through their tender story.

“What needed to be correct was the emotional truth of the play,” Michelle said. “It’s an emotional truth that anybody can relate to, even if you’re not Black. I’d like to think there is a white parent or grandparent sitting in the audience thinking, ‘I’d be furious if my little kids couldn’t get into Fairyland because of the color of their skin! An amusement park, of all things!’ ”

Opened in 1923 on 80 acres at 75th and Prospect, Fairyland declined in popularity during the 1960s and closed its gates four years after Worlds of Fun opened in 1973. Inspired partly by an event in Michelle’s childhood, when her mother balked at taking her to Fairyland even when she could have, the play contains elements of magical realism that have marked many of Michelle’s works. It also features flash-forwards to present-day Kansas City, where 17-year-old Ella (who is Rose’s granddaughter) uses smarts and spirit to wage a personal battle against bullying in her school.

Past and present are joined in a manner designed to remind us that, nearly 60 years after the Civil Rights Act, we are still struggling. “This play is about Kansas City needing to be reminded that, just because we’re not in the Deep South doesn’t mean that we didn’t do pretty much all the things that the Deep South did,” Michelle said.

The exclusionary experiences of Jim Crow have formed a crucial part of Michelle’s family history and are found in much of her work, including Only One Day a Year. “A story about a young Black girl, either in modern times or in the ‘60s, fighting for basic equality… despite the color of my skin? Heck, that’s my all-day, every day,” she said with a laugh.

A fourth-generation Kansas City, Kansan, Michelle has worked as a reporter, an employment attorney, an author (among her books is Working While Black), and a nationally known lecturer on diversity. She wrote fiction before catching the playwrighting bug, submitting her first theater piece to the Barn Players’ annual 6 x 10 Ten Minute Play Festival in 2011. She is currently associate talk show producer for National Public Radio’s Louisville Public Media.

Michelle was born in 1964, and for all her achievements she remains aware that “if I had been an adult the year I was born, I wouldn’t have been able to do 90 percent of the things I’ve done… to have the degrees I’ve had, have the jobs I’ve had, or lived in most of the places I’ve lived.”

All of the characters in Only One Day a Year contain personal resonances for Michelle. “There a little bit of me in every character,” she said. “And anybody who knows me knows that my grandmother is like the through-line in all of my plays, even if there isn’t an older Black woman in the play.”

Cliffie Marie Owens, who died in 2016, was “one of the wittiest, sharpest, kindest people the world knew,” Michelle wrote of her grandmother, in a profile for The New York Times Magazine. “Her personal superpower was incisiveness laced with a humor that could leave you bent over laughing, yet thinking for days.”

In this play, echoes of Cliffie are strongest in the character of Adult Rose (played by Sherri Roulette-Mosley), who is advising her media-savvy granddaughter, Ella Wilson (Daphany Edwards), on how to raise Cain when necessary. Rose’s widowed father, Bernard James, is played by the same actor (L. Roi Hawkins) as Ella’s prickly school principal, and Oletha Smithfield (Teresa Leggard, who also co-directs, with Sidonie Garrett) is the duplicitous Fairyland employee who tries to uphold the park’s policies even when they go against her own interests.

Central to the story are Rose, Frank (Patrick McGee, Jr.), and August Butler (Frank Charles Dodson), the latter a kindly lodger at the James family’s boarding house. August is a musician, “humorous, trustworthy, with a bit of an old-world quality about him,” Michelle writes. “He’s got a little bit of magic about him, especially when he plays music.”

Even the character of August (who gives Rose an item that allows her to connect with her own internal magic) draws on Michelle’s experience. “There’s a little bit of my grandfather, a little bit of my grandmother,” she said, “and a bit of my uncles: charming, dashing rogues.”

—By Paul Horsley

Only One Day a Year runs through March 5th at The Coterie Theatre, Crown Center. For tickets call 816-474-6552 or go to thecoterie.org. To reach Paul Horsley, performing arts editor, send an email to paul@kcindependent.com or find him on Facebook (paul.horsley.501) or Twitter/Instagram (@phorsleycritic).