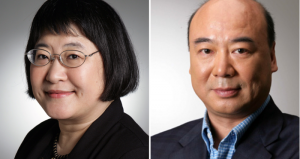

MAHLER AND BEYOND: Stern and DiDonato contemplate the composer’s far-reaching vision

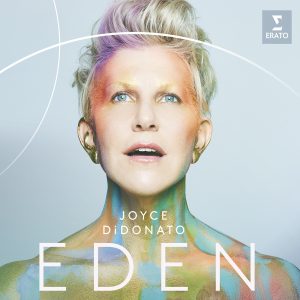

The music of Mahler has formed an important part of Michael Stern’s repertoire throughout his nearly two decades as music director of the Kansas City Symphony. For mezzo-soprano Joyce DiDonato, the Prairie Village native who soared to the top of the opera world 25 years ago and has remained there ever since, Mahler is a fairly recently “departure.”

This weekend (January 12-14) at the Kauffman Center, Joyce appears with Michael and the Symphony in a program of music by Mahler, Ives, Joel Thompson, and others. And in anticipation of the event, we have asked each of them to answer some questions about Mahler and his legacy. Their answers are found in the Q&A portion below.

What a different world we live in from that of 1960, when Leonard Bernstein asked a New York Philharmonic Young People’s Concert audience: “Has any of you ever heard of Mahler? I’ll bet not.” He went on to say that “Mahler isn’t one of those popular names like Beethoven or Gershwin or Ravel.”

Today, Mahler is all around us. More than six decades after Bernstein brought it back to New York Philharmonic audiences, Mahler’s music has taken on a central role in our concert life that is similar, perhaps, to that occupied by Beethoven a century ago.

It is also found in films and on television: In addition to the famous use of the Fifth Symphony’s Adagietto in Death in Venice, Mahler appears prominently in Martin Scorsese’s Shutter Island, Alejandro Iñárritu’s Birdman, FX Networks’ Fargo, a 2016 Gucci Guilty commercial, and most recently in Bradley Cooper’s Maestro, especially in the climactic scene of the “Resurrection” Symphony finale.

And just as Beethoven’s music disrupted Classicism in a way that the 19th century connected with, Mahler’s symphonies contain emotional, textural, and sonic extremes that looked forward to the angst of a century that he would barely live to see. Mahler died in 1911, but he uncannily foretold the wars and terrors of the 20th century “like a camera that has caught Western society in the moment of its incipient decay,” in Bernstein’s words.

This January 12th through the 14th, Joyce DiDonato pays a visit to Michael Stern and the Kansas City Symphony for a program that features Mahler’s Lieder einer fahrenden Gesellen (Songs of a Wayfarer) and “I Am Lost to the World” from the Rückert-Lieder. It is an inspired departure for the Prairie Village native, who has made her astonishing international career singing chiefly 18th- and early-19th-century opera and the occasional song recital with piano.

“I never really expected to sing Mahler,” Joyce said in a recent video on Instagram, in which she discussed the Rückert-Lieder she was about to sing that week with the Vienna Symphony. “I kind of thought that Mahler belonged to other people. However, when the pandemic started … and lockdown happened, this was the only music I wanted to play.”

Like many of us, Joyce spent much of her pandemic down-time at home, reading and puttering around the garden. “But when I sat at the piano, this is the only music I wanted to play, and I kind of ‘got it.’ I think there was something about where I am in my life, and where the world was, that this made a lot of sense.”

Mahler is certainly music for those seeking answers to big questions, and Michael has built this program more broadly around “the idea of existence itself,” as he has stated in a video about the concert: which also includes Charles Ives’ The Unanswered Question in a version Joyce has devised in which she actually sings the trumpet part.

“We’ll delve into Tracy K. Smith’s evocative poems, set so gorgeously by Joel Thompson in his new work The Places We Leave,” Michael continued. And with the Mahler songs, he and Joyce will strive to reveal the composer’s “sublime expressions of grief, of love and loss, of loneliness, of the joy and wonder, the beauty of nature and the search for inner peace.”

Whither music? Bernstein asked, in his 1973 Charles Eliot Norton Lectures at Harvard University. For the late conductor, who seemed to be arguing for the continued relevance of tonal music, Ives’ unanswered question might be construed as: Where does music go from here?

The Unanswered Question from 1908 was composed just months before Arnold Schoenberg famously abandoned tonality altogether, in his Three Piano Pieces, Op. 11 (1909). Ives juxtaposes richly tonal string textures with increasingly dissonant wind passages, as if to ponder which might “win.”

And as Bernstein suggested, it was Mahler’s final works, especially the Ninth Symphony and Das Lied von der Erde (also from 1908-1909), that stretched tonality to a breaking point from which atonality almost seemed to spring.

Mahler’s music has accounted for some of the most memorable moments of Michael’s tenure with the Kansas City Symphony: as he has traversed nearly all the major works, some more than once. The January program is not the end of his Kansas City Mahler connection, though. For his penultimate concert as music director (June 14th through the 16th) he brings us the Symphony No. 2, the “Resurrection”: an upbeat ending to a remarkable 19-season tenure.

—By Paul Horsley

PH: How has this music become so vital to our music life since Bernstein commented to the Young People’s Concert audience that Mahler “isn’t one of those big popular names”? What are the things that brought about that shift?

Michael Stern: One of the main reasons why Mahler became so ubiquitous is the simple fact that earlier in the 20th century, it wasn’t programmed or played very much. Despite the claims, it is not true that Bernstein brought Mahler back from obscurity. Mengelberg, Bruno Walter, Mitropoulos, Szell, and many other conductors included Mahler on their programs. It is true, however, that Bernstein was an unusually compelling champion for this music; for example, even though Mahler had been the music director of the New York Philharmonic in the opening decade of the century, it was not until 50 years later on Bernstein’s watch that a complete traversal of the symphonies and Das Lied von der Erde was presented in New York.

That said, there are other reasons why Mahler is now popular. For one, more and more, audiences like spectacle, and Mahler’s symphonies are spectacular. He throws everything into his works — he famously said that a symphony should encompass the entire world — and he aimed to fulfill that expectation, throwing in everything but the kitchen sink. That eclecticism is also part of Mahler’s appeal to modern audiences. Perhaps most convincing, however, is the argument that Mahler’s now familiar music is also extraordinary, powerful and beautiful. It is moving because it is so human, and that resonates, at least for me, more and more with each passing year.

Mahler seems to have foretold the terrors of the 20th century. What do we make of the conundrum that someone who died in 1911 so uncannily anticipated the angst and the extremes of the 20th and early 21st centuries?

I don’t see it as a conundrum — I don’t think there’s anything paradoxical in why we can be so moved by Mahler today. I certainly would agree that Mahler was prescient in a way, but not necessarily because he foretold any specific events or trends that would unfold after he died. What he did do so well was to immerse himself profoundly in his world in an indelibly authentic way; personally, but then translating each intimate emotion into a more universal expression. His joy, his sardonic skepticism, his profound grief, all specific to him, can be felt by all of us, even today.

The age in which Mahler lived and worked saw some of the most rapid and transformational change in our world history, certainly in Western terms. Mahler caught the Zeitgeist of his era more viscerally than almost anyone, and the Weltschmerz that was so much a part of the fin-de-siècle age and is caught so perfectly in his music resonates with us today.

In the end, I think it’s that authenticity that ties us to him so deeply and will continue to be important to us. In an increasingly digital world, divided among us and disaffected with our traditions and institutions, we are instinctively needing human connections which can sustain us and to which we can cling. Mahler’s vulnerability, humanity, and his weaknesses and strengths all give us those connections.

Every orchestral musician today is expected to have mastered the difficulties of Mahler’s music: How have these demands impacted the overall level of playing: and to that end, the manner in which instrumental playing is taught in conservatories and universities?

It’s not just Mahler’s music — complex though it is, there is other music in our repertoire even more challenging. Yes, the length and breadth of his scores demand unusual stamina and dexterity, but never before has there been such a diversity of genres and vernaculars in all music as there exists today. Precisely because of that need for unfettered virtuosity and an open mind, musicians have simply become technically proficient with each passing decade, and they are taught to welcome and digest everything that is put in front of them.

The level of excellence among young musicians today is phenomenal. That is clearly in evidence in the Kansas City Symphony — after almost 20 years as music director, I have witnessed the evolution of the orchestra and the meteoric rise in its technical and artistic level, and it is inspiring.

And how has it changed the nature of conductor training today, in contrast to that of 50 years ago?

That is a more convoluted question. Conductors as well have to be more open to a vast array of styles, formats, and genres, and they sometimes need to learn techniques specific to contemporary music. That said, the basics always apply — technique, knowledge from real study, the ability to listen closely and critically, communication, inspirational insight, leadership — except for the first attribute, all of those things come from within, and are hard to teach. I feel most lucky that in my life I had extraordinary teachers, and peerless role models and mentors. In a time when surface is sometimes valued over substance, those things can sometimes be glossed over, and that doesn’t serve the musicians, the music, or the audience.

De Kooning used to say that the past didn’t influence him, he influenced the past. How has the prevalence of Mahler’s music today altered the way we hear Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms, Schumann?

Honestly, I’m not sure it has. I think the sum total of all of our experience, and all the attendant music that comes with that, changes the way we hear everything. I still think one should try to understand and recreate Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms, and Stravinsky the way they were imagining their music in their own time, but I also feel we have a responsibility to allow the recreation of their music to have real impact for us now.

Is there one Mahler work that speaks to you in an especially profound way?

There’s very little Mahler I don’t revere. The songs that Joyce DiDonato will sing, the Lieder einer fahrenden Gesellen, are so profound, and the Rückert-Lieder song “Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen” (“I am Lost to the World”) takes your breath away. Among the symphonies, only the Eighth would be one that I would put on a lower pedestal, despite its impressive impact. I feel completely close to Symphonies Nos. 1, 4 and 5, always. Nos. 3 and 9 are life altering.

The Resurrection symphony, however, looms large for me. Mahler was not a particularly religious sort, and his symphony, despite the title, is exalted not in ecclesiastical ways but in the most human expressions of hope and love. I couldn’t think of a better work to include in my last season in KC than the Symphony No. 2, and we haven’t presented it in quite a few years, so it was the perfect choice for my penultimate concert as music director.

PH: How did you come upon the idea of combining the Joel Thompson piece with the Wayfarer Songs and “Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen”?

Joyce DiDonato: This was Michael’s idea entirely, and I was thrilled when I understood his vision for this concert. Both the Mahler songs and Joel’s extraordinary piece are looking at a world that has shifted, that no longer looks the same to the “wanderer,” and the struggle to find the way forward into a real unknown. There is deep aching and longing for what was, but also a beautiful comprehension present in each of these pieces that one cannot go back to what was. That one must meet the world as it is now, through grief and acceptance, if peace is to be found.

What are some guiding principles toward programming Mahler songs on an orchestral concert?

I’ve just begun my artistic relationship with Mahler and am only now coming to know what it is to sing these pieces with orchestra, and it is an extraordinary sound world that elevates the emotion dramatically. Mahler is so inherently symphonic, that even his simple songs sound as if they could develop into a new symphony (and in fact, some of his vocal themes do just that). I think it gives the audience a great chance to confront the big themes of life and love within themselves, and for my money, that’s exactly what I want out of a concert. I want to leave with a greater understanding of my human condition!

The Wayfarer Songs are often, though not always, sung by men. To what extent do they take on a different meaning when sung by a woman? Or are such generalizations misleading?

I don’t know that I’ve ever really thought about whether any given piece is sung by a man or woman. As a mezzo-soprano I’ve had the great pleasure of crossing all kinds of boundaries, and the artistic freedom that has brought me I wouldn’t change for anything!

The beauty that lies in “someone” singing these songs is that they immediately take on a human quality that is unique—and yet, universal: love, loss, conflict, grief, acceptance. I’m a big fan of people growing in empathy and seeing themselves in another’s story. That’s what’s possible with these songs, no matter who sings them.

What are some of the things that might have brought about a shift in our present view of Mahler’s music, making it practically ubiquitous today?

Ah, I’m not really sure, to be honest. Surely the film Maestro has now cemented his prominence in our culture. It’s been wonderful watching the two stars of the film speak of their discovery of Mahler. Even for me, I didn’t truly start to forge a real understanding of his music until recently. Perhaps Mahler is an arrival point – that you find him when you’re ready? Or it could be that someone hears one of his masterpieces out of the blue and is forever changed!

What are the special vocal demands that Mahler’s music presents?

I can say that as a singer, it requires everything that you are. From a purely technical standpoint, the breath requirements are daunting and intimidating. His phrases NEED endless breath so they can suspend and unravel in a particularly finessed way. But perhaps even more challenging is a sense of trust that, similar to Mozart, you can simply allow his music to unfold without adding much of yourself into the mix.

For my taste it asks for a certain kind of purity that can be effusive, and one that requires you to simply serve the text and phrasing, rather than indulging or presenting. When that balance is struck, time really can stand still.

For Kansas City Symphony tickets, call 816-471-0400 or go to kcsymphony.org. To reach Paul Horsley, performing arts editor, send an email to paul@kcindependent.com or find him on Facebook (paul.horsley.501) or Twitter/Instagram (@phorsleycritic).