EARTH TONES: New generations of American Indian composers are steeped in classical and Native cultures

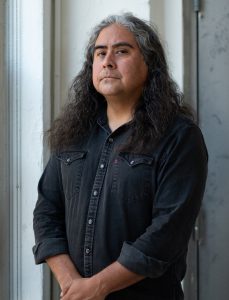

When Raven Chacon won the Pulitzer Prize for Music in 2022, the announcement surprised many American music-lovers, few of whom realized how strong the tradition of concert music by Native Americans had grown during the past two generations.

This year Raven was also awarded the MacArthur Award, given (as the MacArthur Foundation wrote) for “creating musical works that cut across boundaries of visual art and performance to illuminate landscapes, their inhabitants, and histories.”

Now people from all walks are seeking out Raven’s music: not just the Voiceless Mass for which he won the Pulitzer Prize, but also the Three Songs, scored for three women singing in indigenous languages; or the opera Sweet Land (2020), which had its premiere in a state park; or American Ledger (No. 1), which depicts colonialism and the erasure of Native culture.

Suddenly there is great interest in Native American “classical” composers, of whom there are quite a few. Conservatory-trained and closely tied to their heritage (Raven is a member of the Navajo, or Diné, Nation), they are creating a sensation in concert halls and on recordings.

Much of the music is socially and historically conscious and steeped in Native American tunes, rhythms, and texts. One can only dream that this new awareness of enormous creativity might help all Americans come to terms with the plight of people who have been driven from their native lands for five centuries.

All eyes are on creators such as flutist-composer Brent Michael Davids of the Stockbridge-Munsee Mohicans, the Ute-Navaho flutist R. Carlos Nakai, the Mohawk cellist-composer Dawn Avery, Navaho composer Michale Begay, or pianist-composer Jerod Impichchaachaaha’ Tate of the Chickasaw Nation in Oklahoma.

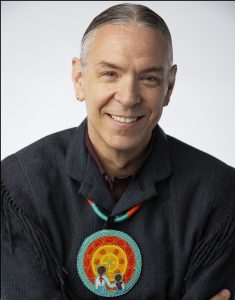

Jerod’s Shakamaxon received its local premiere by the Kansas City Symphony in 2021, in an online-only performance that nevertheless made a strong impression. Today he is one of the busiest composers in America, with commissions that stretch out for several years.

“There are so many artists in Indian country, in all the genres you can think of,” said Jerod, who earned degrees from Northwestern University and The Cleveland Institute of Music, of the abundance of Native American arts today.

“In all the visual arts, choreography, literature, theater, and of course filmmaking.” This flowering of the arts is not new: “This has been going on for a long time.”

Until about a century ago, though, indigenous music heard in American concert halls was not by Native Americans at all. Antonín Dvořák was not the first to use melodies that he imagined were Native tunes (in works he wrote during his “American years,” 1892-1895), but his music was the first of its kind to have international impact: especially his “New World” Symphony, whose success many composers have tried to emulate.

Other composers were inspired by the work of “ethnologists” such as Natalie Curtis, who during the early 20th century visited the Hopi and other communities in the Southwest and published neatly transcribed tunes in a volume she called The Indians’ Book. It became a source for those who admired the sort of “exotic” appeal these tunes lent to classical works, much as earlier generations of Europeans had used materials from the Middle East or Asia.

Composers such as Percy Grainger, Charles Wakefield Cadman (From Wigwam and Teepee), Edward MacDowell (Indian Suite), and Ferruccio Busoni (the Indian Fantasy for piano and orchestra) used Native tunes with a sort of ingenuous naiveté.

“What they were doing were acts of curiosity,” Jerod said. “And that’s fine, but when the rubber hits the road… they just didn’t do it well.” Indeed, with the exception of Dvořák, whose “American” music was as much Czech as it was American, none of these composers (whom some have dubbed “Indianists”) created much of value.

Jerod, a classically trained pianist and composer, notes that almost none of them showed any interest in actual contact with Native Americans. Edward MacDowell, for example, would use tunes that had been passed down third- and fourth-hand to the point where “there was actually zero connection to the source. He had no experience with it.”

Works of the past remain of historical value, though, and some composers used Native materials in a spirit of veneration: however naive their intentions. “I think some of them are still okay to play,” said Robert Folsom, a Kansas City journalist, musician, and classical music fan whose father was Choctaw and whose mother was Lakota from the Rosebud Sioux Tribe of South Dakota.

Robert compared the ethnographical work such as that of Natalie Curtis to the research of Bartók and Kodály in Eastern Europe in the early-20th century: work that unearthed tunes the composers later used in their own compositions. “As long as it’s used as source material, even if it is only a motif,” Robert added, and not stolen wholesale. “It’s fine with me as long as it is not used in a stereotypical, cliché-sounding manner.”

Louis W. Ballard (1931-2007) of Miami, Oklahoma was to change the landscape of Native music forever. Son of a Quapaw mother and a Cherokee father, this “Father of Native American Composition” studied piano, music theory, conducting, and composition at the University of Tulsa. He later worked privately with master composers Darius Milhaud and Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco, and he was a frequent guest at the Aspen Music Festival. He was the first American Indian to earn a doctorate in composition.

Louis was not shy about confronting difficult issues: His Incident at Wounded Knee was performed in 1974 in St. Paul, Minnesota, with Dennis Russell Davies and the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra: a year after the protest occupation on Pine Ridge Reservation.

He made a mark in Kansas City, too. In 1975, the Kansas City Philharmonic gave the world premiere of the composer’s Portrait of Will Rogers, with Will Rogers, Jr. as narrator. In 2000, Louis was distinguished visiting professor at William Jewell College.

Many Native composers today point to Louis as an inspiration. He was a consummate composer who refused to be pigeonholed and wrote beautifully crafted works that were challenging yet accessible.

“For me, it was the fact that he existed at all,” said composer Brent Michael Davids, in a recent interview on the Chicago Symphony website. “I was studying all these different composers from everywhere and all different periods of history, and here’s Louis.”

Today’s Native American composers are as varied in outlook and aesthetic as the more than 500 tribes they represent. “Every single person on this planet has an incredibly robust and rich experience that is unique to that person,” said Jerod, adding that his own influences have included Motown, Duke Ellington, John Coltrane, George Crumb, and the drum and bugle corps of his youth. The son of a prominent choreographer (Patricia Tate), he also looks to great dancer-choreographers of the early American tradition: Isadora Duncan, Martha Graham, Agnes de Mille.

It was his Manx Irish mother who first commissioned a work from her son, which became her ballet Winter Moons. It was perhaps the first time Jerod realized he was the result of everything he had lived: from Beethoven to Ballard, Cage to Coltrane to the art and songs of his people. “She asked me to be all of who I am, all at the exact same time. And it made total sense.”

To reach Paul Horsley, performing arts editor, send an email to paul@kcindependent.com or find him on Facebook (paul.horsley.501) or Twitter/Instagram (@phorsleycritic).

By Paul Horsley