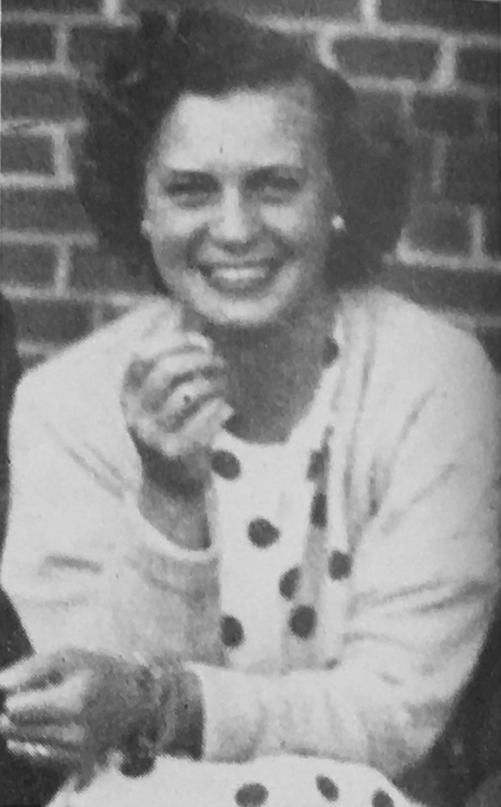

A Toast to Olde Tymes – Mary Conover Mellon

Reprinted from the October 19, 1946 issue of The Independent.

Mary Conover Mellon lived much of her life away from Kansas City. Her memorial still stands, decades after her death. It is a building on what is now the lower school campus of The Pembroke Hill School, which was the Sunset Hill School in her lifetime. In all likelihood, though, many of the students who have passed through the doors have known little about her.

Mary was born on May 25, 1904. She was the daughter of Perla Petty Conover, who had trained as a nurse, and Dr. Charles C. Conover. Mary and her younger sister, Catherine, both attended Sunset Hill, graduating in 1921 and 1930, respectively.

According to William McGuire in Bollingen: An Adventure in Collecting the Past, “She studied French from kindergarten on, took piano lessons, edited the school magazine, but shied away from sports.” In childhood, Mary was troubled by asthma attacks, a situation which was exacerbated by being around horses, and, in some cases, by social occasions. Mary and her father shared an interest in psychosomatic disorders. It seemed possible to them that her condition might involve both physical and mental aspects, and that it might improve once they were understood and addressed.

Mary attended the Bradford Academy for one year before going to Vassar College. While there, French and music were her main interests. After graduation, she continued her studies in French at The Sorbonne and Columbia University. She married Karl Stanley Brown, a Yale graduate from Allentown, Pennsylvania. Karl worked in advertising; Mary managed an art gallery. The couple divorced in 1933. It goes without saying that divorce carried far more stigma in American life in the early years of the 20th century than it does now.

Paul Mellon, destined to be Mary’s second husband, hadn’t been married before, but he had been a child when his parents divorced. His father was Andrew Mellon, the financier and art collector who served as secretary of the treasury during three Republican administrations. In his forties, Andrew wed Nora McMullen, an English girl half his age. Their daughter, Ailsa, was born in June 1901, and Paul in June 1907. The marriage was rocky from its earliest stages, and it has been acknowledged that Nora was in love with someone else for many of the years that she was Andrew’s wife. When the end came, Andrew spent more than $100,000 on legal fees. Their divorce was final in 1912. The custody arrangement was that the children were to spend eight months per year with their father, and the remainder of the time with their mother.

Paul, who was three years Mary’s junior, was a graduate of The Choate School and Yale University. He continued his studies at Clare College, Cambridge, in England. Like his father, he would collect art, starting with a painting of a horse by George Stubbs. Horses: Paul loved them. Less of interest to him was the family business. He went to work for Mellon Bank when he finished school, mainly in the hope of pleasing his father.

Mary and Paul were introduced to each other in December 1933 by Lucius Beebe, whom Paul knew from Yale. Lucius was a well-known journalist of the era, who was openly gay. As Paul recounted in his memoir, Reflections in a Silver Spoon, “He said he had a luncheon engagement with a very nice girl called Mrs. Brown, and why didn’t I come along and join them?” At the end of a very enjoyable afternoon, Paul took Mary to dinner – minus Lucius. Within months, the two were engaged.

February 2, 1935, was their wedding date. The intimate ceremony took place in New York, at the Sutton Place home of Paul’s sister, Ailsa Mellon Bruce, and her then-husband, David Bruce. (David would go on to hold a series of ambassadorships, but that would be after his divorce from Ailsa.) Both of Paul’s parents were present, along with the Conovers. Catherine Conover Bunting (Mrs. Clarke S. P. Bunting) was her sister’s attendant, and David Bruce stood up with his brother-in-law. Dr. Conover gave the bride away. The ceremony was held in the living room, which was festooned with cherry blossoms and calla lilies. Other rooms were decorated with tulips and jonquils. (In 1935, it would have been a sign of opulence just to have these flowers, none of which were blooming in New York in early February.) After the couple exchanged their vows, breakfast was served to family members and friends. Wedding cake? Of course. Following an English tradition, there was a bride’s cake, which featured fruit and was topped with white icing. A long honeymoon abroad was next on the newlyweds’ agenda.

One of Paul’s early gifts to Mary was a racehorse. She still was troubled by asthma, but only intermittently. Despite the fact that she had a bad attack after visiting a racetrack while they were engaged, they both hoped that part of her problem might be psychological. That led Mary and Paul to enter Jungian analysis, eventually with Dr. C. G. Jung himself. Years later, in 1945, Mary and Paul created the Bollingen Foundation. It was named for a village in Switzerland where Dr. Jung spent much time. Mary’s goal was to ensure that the doctor’s writings were translated into English. She was the first president of the Foundation and the first editor of the Bollingen Series, which included Dr. Jung’s work, and was published by Helen and Kurt Wolff of Pantheon Books.

No one can predict on a couple’s wedding day exactly what the future will bring. For Mary and Paul, there would be the births of two children, Catherine Conover Mellon in 1936 and Timothy Mellon in 1942. Their vast wealth meant that they could travel the globe, and then come home to a variety of properties, including Oak Spring, an estate in Virginia that remained in the family for more than 70 years. Late in 1936, Paul had a serious conversation with his father. As a result of that, he felt more comfortable about pursuing his own interests, rather than devoting himself to business. The timing was fortuitous: Andrew died in 1937. Prior to Andrew’s death, he had begun creating the National Gallery of Art; Paul would be involved with the museum throughout his life. During the early years of World War II, Paul joined the United States Army. He served in the cavalry and was stationed at Fort Riley. Mary and the children spent much time in Kansas City with her parents. After their son’s birth, the Mellons lived for a time in a rental house in Junction City, Kansas. Paul’s next posting was at Fort Hamilton in Brooklyn, New York, enabling them to return to their apartment on East 70th Street in Manhattan. Paul subsequently went to Europe where he joined the Office of Strategic Services (often known as the OSS, it was the forerunner of the CIA). Just like many other young couples, Mary and Paul would endure a long separation during the war.

Paul experienced some difficulties in adjusting to post-war America, finding himself “restless and irritable” on a trip to their house in Hobe Sound, Florida. Writing about it decades later, he recognized that Mary had dealt with many frustrations during the war years. “For Mary, the responsibilities of caring for the children and our two little English evacuees, problems over the supply of labor, the day-to-day responsibility of running the farm, and the overwhelming sense that her intellectual interests… were withering on the vine all served to force her into a state of unrest and depression…” he recalled, adding, “I have a very strong feeling that eventually we would have found a calmer and sunnier common ground on which to continue our lives.”

Mary’s health was a source of worry. Her goal was to overcome asthma, but it wasn’t a matter of willpower. As Paul wrote, “Mary had enjoyed interludes of about two months during the war when she had no attacks of asthma. She even reached the point where she could ride a horse without suffering from any of these symptoms. She had a theory that if she could regain asthma-free comfort while riding, it might lessen the frequency of her seizures overall.” That wasn’t the opinion of their family physician, who told Paul, “You know, this thing can’t go on much longer. It’s a terrible strain on her heart.”

Mary died in October 1946 at Oak Spring. She had spent the morning fox hunting, and was taken ill in the afternoon. Paul was left with two young children. He married again in 1948. His second wife was Rachel Lambert Lloyd, better known as Bunny. Her family fortune came from Listerine. She was divorced and the mother of a son and a daughter. Bunny Mellon became a renowned garden designer and lived to be 103.

It was important to Paul to preserve Mary’s memory. Paul donated the Mary Conover Mellon Building to Sunset Hill, her alma mater. The dedication was held in September 1949. Paul laid the cornerstone. According to The Kansas City Times, in his speech he noted that “he had heard a great deal about the Sunset Hill school from his wife, but that he had never visited the school until Tuesday [two days before the ceremony]… Of the new building, he believed that it would become a visible symbol of Mrs. Mellon’s own belief that education was ‘a tool for making the mind clearer and the heart more understanding.’” Neville & Sharp, architects, designed the building, which was estimated to cost $95,000. It opened at the end of April in 1950. It was not Paul’s only gift to a Kansas City institution in honor of a member of the Conover family: he donated a medical laboratory, which was dedicated in 1954, to Trinity Lutheran Hospital. The laboratory was named for his father-in-law, Dr. Conover, who was on the staff there for more than 30 years.

Paul continued to support the Bollingen Foundation and the Bollingen Series. The Collected Works of C. G. Jung ultimately spanned 21 volumes, which were published between 1953 and 1979. The Series included other titles, with perhaps the best-known being The I-Ching, or Book of Changes, which enjoyed a wide readership beginning in the 1950s. Princeton University took charge of the Series and the Foundation in 1967. (The Bollingen Prize for Poetry, which is a separate entity, was founded by Paul in 1948.)

When Paul died in 1999, his obituary was front-page news. John Russell, the art critic, gave readers of The New York Times a capsule summary of the family’s philanthropy, much of it orchestrated by Paul: “The Mellons’ total contributions to museums and other causes from parks to poetry has been estimated at nearly a billion dollars.” Because Lucius Beebe invited Paul Mellon to lunch with Mrs. Brown, some of those funds came to Kansas City.

For further reading:

* Cannadine, David. Mellon: An American Life. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2006.

* McGuire, William. Bollingen: An Adventure in Collecting the Past. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, year unknown. Google Books.

* Mellon, Paul with John Baskett. Reflections in a Silver Spoon. New York: William Morrow and Company, 1992.

Features

When Martha Deardorff Shields and Edwin W. Shields began building Oaklands, they had been married for more than a dozen years and were the parents of a daughter and a…

Who remembers Alexander Woollcott? For some, what comes to mind is that he was a member of the Algonquin Round Table and a writer for The New Yorker magazine during…

The third floor of Emery, Bird, Thayer was the site for a May 1937 fashion show featuring everything from beach togs to gardening overalls to bridal dresses, as they were…