CONQUERING CONCORD: Broadway musical confirms wide appeal of Alcott classic

The impact of a book can often be gauged by the number and variety of adaptations it spawns. Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women was published more than 150 years ago, but it continues to feel like an archetypal portrait of at least one kind of American family. The Civil War-era tale of the struggling March family in Concord, Massachusetts, has inspired dozens of stage adaptations, literary spinoffs, children’s versions, television series, radio plays, and a half-dozen films dating back to the silent era.

In 1998, Composer Mark Adamo adapted it into one of the most successful American operas of the 20th century, which has appeared on Kansas City stages more than once. And, in 2005, it became the source for a sure-footed Broadway musical, with a book by Allan Knee, lyrics by Mindi Dickstein, and music by Jason Howland.

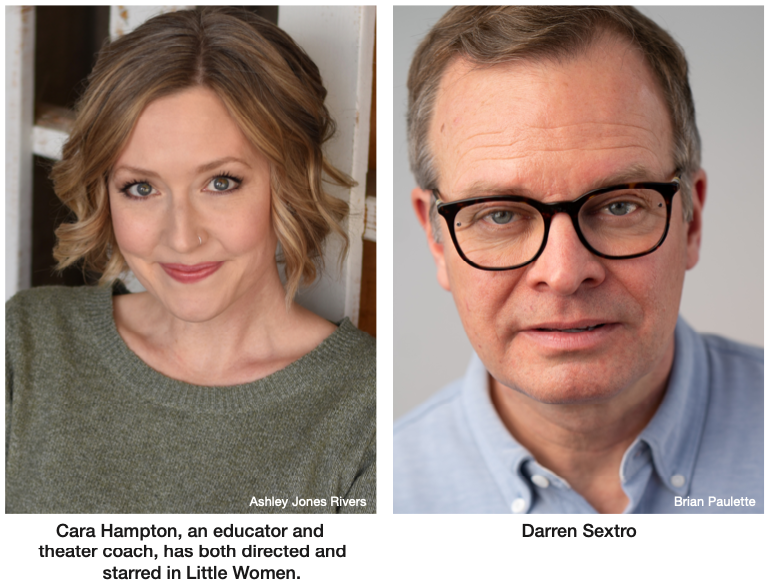

“It’s essentially a coming-of-age story about four sisters,” said Cara Hampton, who directs The Barn Players’ production of the musical in August. “And we had more than 100 people auditioning for it.” The musical “had been on our list for several years,” said Artistic Director Eric Magnus, “because of the universal story line, the beloved characters, and the quality of the score. However, the biggest driving factor was the opportunity to showcase the many great actresses who are part of the Kansas City metro community.”

Little Women has long been viewed as a story for girls and young women. (During my formative years, boys read the Hardy Boys and The Call of the Wild, girls read Nancy Drew, the Brontës, and Little Women.) Today, we are more inclined to see the universality of its themes, and of its characters: Meg is traditional and beautiful and marries young; Jo is a writer and free spirit who defies gender stereotypes; Beth is sweet and honest and a gifted pianist; and Amy is the coddled youngest child who loves fine things and yearns to live well.

Many adaptations focus on Jo as a bold central figure, but Cara likes to bring sensibilities of the novel to the story. “In the musical, and in most of the movie adaptations, Jo gets most of the attention,” Cara said. “In the book, you read quite a lot about all of the sisters, each coming of age in her own way.”

Jo does often feel central to the story, perhaps because she is a portrait of Louisa May Alcott herself, but in the long run “you cannot separate who the sisters are individually from the experiences they have with each other,” Cara said. “And we all know how true that is, how our own families and our early life experiences shape us. … Jo is who she is because of everyone around her: She is a product of her community and her family.”

What Cara appreciates about the novel “is how all the girls’ different paths are explored, and none of them seems to be glorified over the others.” What rubs her the wrong way is how some adaptations create a false dichotomy between “liberated” Jo and well-settled Meg. The eldest March sister is often seen “as a kind of throwaway character,” Cara said, “sort of an opposite, a foil for Jo. Meg is the one who grew up and got married and did all the things everyone expected her to do.”

Rereading the novel, Cara came away with a very different concept of Meg, who willfully chooses marriage and children because it is the path she wants. “It’s what she’s good at, she loves it, and it makes her happy. … She serves the people around her with the gifts and talents she has.” (As Meg says to Jo in the book: “Just because my dreams are different from yours doesn’t mean they’re unimportant.”)

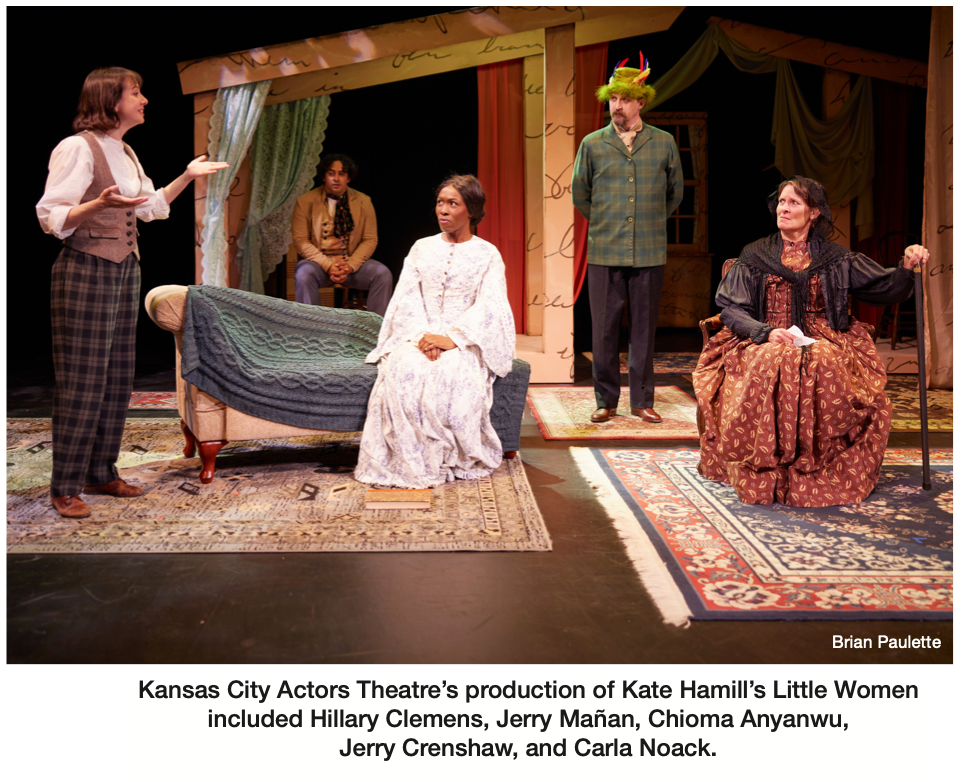

But Cara also understands the impulse to leave Jo single. “This independent woman with dreams and ambitions, who supports her family at a time when that was uncommon… appeals to a modern feminist audience,” Cara said. In Kate Hamill’s version, which Kansas City Actors Theatre staged this spring, Jo strikes out on her own, as it dawns on her (perhaps) that she is “gender-queer or non-binary,” as Kate has said: somewhat in keeping with what we know about Louisa May Alcott. “When Kate somewhat alters the story, she does it by leaning into Louisa May Alcott’s life,” said Darren Sextro, who directed the Actors Theatre production. “Which makes it more about Louisa May Alcott and less about the adapter.”

In other retellings, including both George Cukor’s 1933 film and Greta Gerwig’s Oscar-winning version, the question of whether Jo marries remains ambiguous. (Still, nearly everybody agrees that it makes more sense for Jo to join with like-minded Bhaer than with moony Laurie.)

The 2005 musical takes a traditional route, but it also uses music to convey, with remarkable efficiency, character quirks and emotional states. “Little Women is a gigantic book, and with any adaptation you have to cut away so much,” Cara said. “Adding a song is a great way to propel the story, and to add emotional heft when you don’t have a lot of time.”

Music “can help the audience know, very quickly, what they should think about something,” she said, “or draw attention to certain things purposely, guide the storytelling in ways that you can’t do with just text.” The Act I duet between Jo and Aunt March (“Could You?”), for example, adopts an operatic style to convey the latter’s haughty high-mindedness. “Any time there’s an operatic style of singing, it’s used for comic or satirical effect,” Cara said. “The sincere or genuine moments are more in the musical theater mode.”

The Barn Players’ Little Women will run from August 11th through the 20th at Johnson County Arts & Heritage Center. It stars Miranda Brand, Larissa Briley, Abbey Downs, Mia Cabrera, Ginger Birch, Henry Morgan, and Zak Smith. Call 913-432-9100, or go to thebarnplayers.org. To reach Paul Horsley, performing arts editor, send an email to paul@kcindependent.com or find him on Facebook or Twitter, Instagram, and LinkedIn.

Featured in the July 22, 2023 issue of The Independent.

By Paul Horsley