A MOTHER’S WORRY: Chamber opera by two Kansas City-born women is exerting national impact

Most mothers dread the day that their sons or daughters start to drive, but Black moms are especially fearful when their teenagers, and sons in particular, get behind the wheel for the first time.

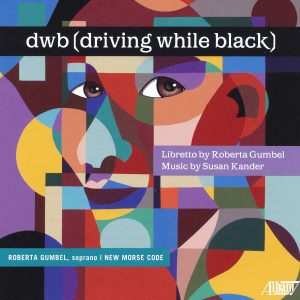

That fear helped spark the inception of a new chamber opera by two internationally known Kansas City natives, Soprano and Librettist Roberta Gumbel and Composer Susan Kander. In the past few years this work has been performed regionally and is now available on a CD recently issued by Albany Records, and in a streamed video created by UrbanArias in the Washington, D.C. area. From June 19th through the 26th the Lyric Opera will stream the Kansas City production on its website for free. (See information below.)

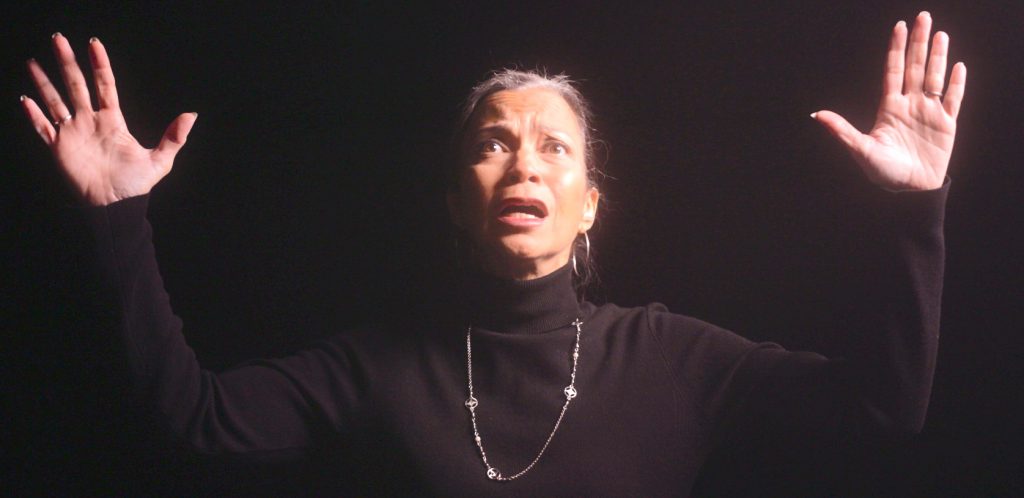

dwb (driving while black) came into existence at around the time that Roberta, a lecturer in voice and opera at The University of Kansas, who has enjoyed a major career on operatic and Broadway stages, recognized that her only son was poised to start driving.

One day when Rapheal was 15 and riding in the car with his mother, she stopped abruptly and ordered him to get out of the car.

“What’d I do?” he asked, thinking he was in trouble. Roberta laughed and handed him the keys. The young man was elated. “And we went forward and backward, no turns,” Roberta said.

“All the kids at that age are talking about driving,” she added. “He was ready, and I guess that day I just decided I can handle it.” After extensive practice in parking lots, Rapheal (who is now 21 and a KU student) earned his license. Roberta has not stopped worrying since. She probably never will. “Do I cower in fear every time he leaves the house? No. But am I aware that the danger is real? Absolutely.”

It was during a subsequent conversation that Roberta had with her longtime friend and musical associate, Susan Kander, that the pair lit upon this topic as fertile ground for what was initially framed as a song cycle. Eventually it grew into a 45-minute monodrama for soprano, cello, and percussion that confronts the dangers that lurk for Black Americans.

Susan, who has made her career in New York but maintains ties to her Kansas City family (her parents were the late Ann and Edward Kander, her Uncle John is the composer of Cabaret and Chicago), was eager to work with Roberta, whose golden voice she has long treasured.

The music department at The University of Kansas had recently hired Cellist Hannah Collins, whom Susan knew through musical circles, and the composer was excited to including her and Percussionist Michael Compitello in the work’s inception. (The contemporary-music duo is nationally known as New Morse Code.)

“This does require stupendous artists,” Susan said of the demanding score she created. “And I don’t apologize for that, because if I’d written an easier score, especially for the instrumentalists, I don’t think I could have accomplished what I wanted to emotionally.”

The onstage presence of cellist and percussionist becomes part of the theatrical conceit: “The sound world offered by voice, cello, and percussion was mesmerizing to me right out of the gate,” Susan said in an interview with classicalmusiccommunications.com this March. “It’s great to break up the timbre and texture of the human voice here and there: It wakes up our ears a bit and widens the dramatic lens terrifically.”

The first performance of dwb, in November 2018 at Lawrence Arts Center, was followed by affecting presentations of the work in January 2019 at the 1900 Building and at St. James United Methodist Church. Roberta, Hannah, and Michael were joined by Stage Director Chip Miller, then artistic associate/resident director for Kansas City Repertory Theatre, who helped make the work into a potent piece of theater.

dwb drew the attention of Ted Altschuler at New York’s Baruch Performing Arts Center, which partnered with Opera Omaha to create a virtual video of the work, filmed at Lawrence Arts Center in October 2020.

Interest in the work has continued to grow. April 30th of this year saw the streaming premiere of a new version: a fully realized film by an Arlington, Virginia-based opera company, UrbanArias, featuring Soprano Karen Slack and directed by Du’Bois and Camry A’Keen. (It is available for viewing at urbanarias.org through October 31st. See information below.)

The authors hope there will be many more such performances. One of their goals, in fact, is to help build repertoire for Black female singers that is portable, inexpensive, “and usable in small spaces and venues,” Roberta said.

dwb follows the first 16 years of a young man’s life. At its core it is the deeply personal (and partly autobiographical) narrative about the relationship between mother and son. Into a succession of “Scenes” is woven a series of “Bulletins” recounting sobering events that have happened either to members of Roberta’s own family or to other Black men and women around the nation.

“A congressman pulled over seven times for driving a nice car,” reads one Bulletin. “A neighbor calls 911 about a man… a man! … parked! parked! In front of his own house!” reads another. The instrumentalists assist the soprano in the storytelling: calling out events, clapping or striking their instruments, and creating propulsive rhythms to illustrate the narrative.

“You, my beautiful brown boy/You are not who they see!” sings the Mother, first quietly and then with increasing intensity as the work progresses. The young man gradually learns that even though he is indeed a beloved son, to some he will always be a potential suspect.

“When I was studying for the driver’s license test, my parents sat me down for an important discussion about car safety,” said Chip Miller in a Director’s Note. “What to do when you are pulled over by a police officer. I’m sure I rolled my eyes. To me, the car represented freedom, and that was all I could see. I could not yet see the numerous times I would be pulled over for being in the wrong neighborhood. … But my parents did.”

For Chip, the piece provided “a window through which to revisit that crucial conversation, this time from the vantage point of my parents.” In the final analysis, he added, “in dwb, the car becomes a place of joy, fear, mourning, and danger. It is a vehicle for healing, our shared experience set to beautiful music.”

The inherent dangers are conveyed in vivid detail in dwb. “Short young man with dreadlocks out with his girlfriend,” runs one of the opera’s Bulletins. “Cuffed! and sitting on the curb, as police realize he’s just not the tall, bald man they’re looking for.” Later the Mother sings: “How can I set you on a path … in this world/In a world that doesn’t live up to its promises/Its promises and dreams?”

Susan, who normally writes her own librettos, quickly realized that Roberta was the natural librettist for dwb. “Roberta is my ideal collaborator,” Susan said. “She has a background in theater that is as big or bigger than mine. … So every moment in this piece is infused with our collective theatrical toolbox.”

As a veteran of the stage, Roberta “understands better than any librettist out there what is involved in walking from point A to point B,” Susan said. “All the things that a performer has to do, and the things that the text and the music have to do in order to ‘get an action to happen.’ It was an incredible experience to write with somebody who packed all that onto the page.”

Roberta had some trepidation about tackling the libretto. “I said, ‘Susan this isn’t what people who go to the opera expect to see.’ Her response was: ‘Well let’s make them see it. Because if this is your world… the opera world and also the world in which you’re raising a Black son… then this piece has its place.’ And I said, Okay, I’m in!’ And as I wrote, she gave me a lot of confidence.”

To be sure, dwb was conceived in the midst of the very turmoil of which it speaks. “But we weren’t thinking of being activists at the time,” Roberta said. “The piece has become something that really provokes that thought. But we were writing a drama about a mother and her fears, and we wrote it before George Floyd was killed. And it’s now so much more in the headlines… people are not able to ignore it.”

—By Paul Horsley

- For more information about Susan see susankander.net, and for Roberta go to music.ku.edu/roberta-gumbel. Information about Hannah and Michael is at newmorsecode.com.

- From June 19th through the 26th the Lyric Opera of Kansas City will mark Juneteenth by streaming a video of the Kansas City production, free to members of its e-club. For information on joining and viewing, go to kcopera.org/driving-while-black.

- A brief excerpt from the opera, the lullaby “My Beautiful Brown Boy” sung by Roberta, can now be viewed on YouTube here.

- Tickets for virtual viewing of UrbanArias’ version can be purchased at urbanarias.ticketspice.com/driving-while-black.

To reach Paul Horsley, performing arts editor; send an email to paul@kcindependent.com or find him on Facebook or Twitter (@phorsleycritic).