HOWL ME A TUNE: As composers evoke animals in their music, orchestral musicians draw symbiotic sustenance from their own pets

Early humans may not have actually learned to make music from the beasts of the air, land, or sea, but they were clearly aware of the sounds around them. We can probably assume that they shared our own fascination with the “songs” of birds, whales, and wolves: even as we recognize that, to whatever extent these vocalizations might resemble music, they are not to be compared to the phrases, textures, and structures produced by human intellect and aesthetics.

But this has not stopped composers from attempting to imitate or at least evoke the sounds of creatures at every possible turn. Homages to animal sounds appear in the music of most world cultures, and in notated Western music they began appearing already in the Middle Ages. By the Renaissance we already had harpsichords imitating the raucous clucking of hens.

Concert composers have continued to delight in such evocations. From the trilling “birds” announcing spring in Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons to the cuckoo in Beethoven’s Sixth Symphony, from the bleating sheep in Strauss Don Quixote to the note-perfect bird-song imitations of Messiaen, these are more than just novelties: At best, they create an atmosphere that is fundamental to the “meaning” of a piece.

Thus while Rimsky-Korsakov’s Flight of the Bumblebee excites the ear because it really does sound like bees, it has stuck around for 120 years mostly because it is a richly crafted piece of music.

The fascination with creatures has continued to delight composers of our time. One of George Crumb’s most endearing works is his Mundus Canis (1998), a suite of five movements for guitar and percussion in which the composer paid tribute to the various dogs his family has loved over the years.

It seems perfectly natural that the modern symphony orchestra with its vast array of sonic capabilities has become the primary “promoter” of this tradition, and it is within the orchestral repertoire that the phenomenon begins to take on a larger significance for all of us. Two works in particular, Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf and Saint-Saëns’ The Carnival of the Animals, have become favorites of young audiences not just because they illustrate stories and mimic animal sounds but because they are marvelous works of art.

“These are all things that kids can relate to,” said Jason Seber, who as the Kansas City Symphony’s associate conductor leads most of its youth and family concerts. “It makes them more active listeners to the musical content of whatever the composer’s trying to say. It’s not just the imitation of an animal, but also: Why this instrument? Why this register of the instrument? Why did the composer pick this? And it allows you to have those kinds of interesting discussions with the kids.”

Kids adore animals, of course, “and they know what they sound like,” Jason said. In the 1936 musical “fairy tale” Peter and the Wolf, “Prokofiev does a great job of picking the perfect instrument for each of the animal characters in the story.”

The flute is the rapid-fire, twittering bird, and the oboe in its lower register represents the recalcitrant, nasal-sounding duck. The clarinet is the crafty cat.

“He finds the instruments that have not only the perfect timbre, but also the character of those animals,” Jason said. “Cats are sneaky, they are mischievous.” And the sinister wolf-theme is famously played by an ensemble of French horns in low register, he added, “which is of course terrifying.”

All this has another, residual effect, of course: Peter also introduces youngsters to the instruments of the orchestra, displaying in detail how the sonorities of different wind and brass instruments, especially, communicate mood and spirit. And these memories tend to “stick.”

“I constantly talk to adults who grew up with this piece,” Jason said. “And they say it was their first experience hearing what a flute sounded like, what an oboe sounded like, what a clarinet sounded like. … And they are still able to identify those instruments every time they hear an orchestra.”

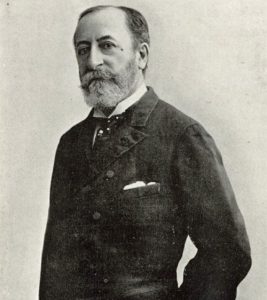

Likewise, in The Carnival of the Animals, which is scored for two pianos and orchestra, Saint-Saëns finds highly inventive ways to represent a veritable zoo-full of animals (14, to be exact).

The Swan, for example (probably the most famous movement of the work) communicates tensile fluidity through a solo cello playing in an oddly high register.

“He could very easily have written that for a violin,” Jason said. “But there’s something about the beauty of the cello in that register that perfectly captures the grace of the swan.”

The quasi-comical double-bass sound “captures something of the weight of the elephant but also the ease with this it moves,” he said. And the shimmering percussion sound of the Aquarium “creates a fascinating feeling of moving through water: To me it feels like you literally can see fish swimming.”

None of this would click, according to Jason, if these pieces were not brilliant scores. Indeed, these two compositions are not merely illustrative in nature, they are coloristic and masterfully structured, and they keep one’s attention from start to finish.

“No matter how many times the orchestra has played the Prokofiev, they love it,” Jason said. “Because it’s a well-written score that, more than anything, helps a kid have a good experience with the music. If it’s quality music, they’re going to respond in a positive way.”

Composers through the ages are known for their distinctive relationships with pets, and this tradition has continued with musicians of the modern orchestra. When Beethoven fell in love with his piano pupil Therese Malfatti, it was apparently only her little dog, Gigons, who returned the affection: following the composer home one night and sitting quietly by his side as he ate dinner.

Chopin’s Minute Waltz was thought to have been inspired by Marquis, the little dog owned by his friend George Sand: which was inclined to chase its own tail in a manner that the piece illustrates all too vividly. (It was originally called Valse du Petit Chien, The Little Dog Waltz). And in commenting on his Airedale’s terrier’s anxiety about the family’s impending move in 1947, Shostakovich said: “I have a theory that dogs lead such short lives because they take everything so much to heart.”

A remarkable number of orchestra musicians of today have pets, too, and for many of them the presence of animals in the house (where many of them spend many hours practicing) is an essential part of their existence.

“Puccini does like it when I play music,” said Jason of his six-year-old beauty, a mixed-breed shelter dog with dominant traits of fox hound. “He enjoys when I’m listening to something classical. He might not always get up, but at least he perks up.” When Jason pulls out his violin and starts playing “live,” however, “Puccini’s definitely more interested in that than he is in recorded music.”

Other musicians find they can’t practice high notes without one or more of their animals complaining. “Several of the Kansas City Symphony musicians have huskies,” Jason said, “and as a breed they tend to react to higher frequencies.” Symphony Principal Harpist Katherine Siochi commented that her husky, Brooklyn, helps reminds her of the higher things in life. “She’s taught me … how you shouldn’t value physical objects so much,” she said recently, with a laugh, on the Symphony’s podcast Beethoven Walks Into a Bar.

“ ‘Oh you really like that rug? I’ll chew it to shreds. That was your favorite shirt? I’ll rip it apart with my teeth.’ I’ve just become a more ‘Zen’ person because of her.”

The Kansas City Symphony’s love of animals will be coming full-circle during an upcoming season, as the ensemble works to collaborate with the Kansas City Zoo on a concert pairing specific animals with works from the classical repertoire that reflect the character of each animal.

The end result will likely include videos of the animals on screens in the concert hall, and music that “captures their personalities, the ways that they move,” Jason said. “Which is another way of thinking about how animals and music go together.”

—By Paul Horsley

For the latest information on concerts and webcasts of the Kansas City Symphony, go to kcsymphony.org or mysymphonyseat.org.

To reach Paul Horsley, performing arts editor; send an email to paul@kcindependent.com or find him on Facebook (paul.horsley.501) or Twitter (@phorsleycritic).